Picture this: a leatherback sea turtle, a quintessentially pelagic animal, casually swimming in a jungle river in Trinidad. That’s right, a leatherback in crystal-clear fresh water with tropical foliage in the background. A freak occurrence? Absolutely. But there it was gliding in front of us, three well-travelled, experienced — and speechless — photographers.

There was no time to waste. This precious opportunity could end at any second, so I went to work, slowly approaching the turtle from the side, careful not to chase or alarm it. When the water got too shallow, I kicked off my fins, tossed my mask aside and walked next to the turtle, shooting from the hip. I was grateful to have a fisheye lens, a huge glass dome and fresh batteries that kept my temperamental strobes happy and firing. Luckily, a rocky bottom — similar to a trout stream’s — kept the water mostly free of debris. My two friends and I took turns, synchronizing our efforts and miraculously staying out of each other’s way.

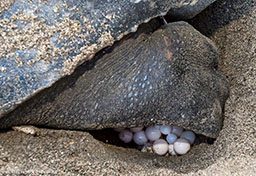

The current washed the sand and salt mucus from the turtle’s eyes and revealed an animal of extraordinary beauty. Not your typical black leatherback, this turtle was a very pale, bluish gray with a constellation of little white stars covering her body. Every 30 feet or so, the turtle lifted her massive head out of the water to breathe the warm humid air and kept going, soaking in her new surroundings. Roughly a half mile from the sea, this living dinosaur finally realized she was in a very strange neighborhood and turned around, eventually making it back to the mouth of the river and swimming into the murky and angry Caribbean.

A 100-million-year-old species, the leatherback is not your ordinary sea turtle — it’s almost an insult to call it one. In a class entirely its own, it is one of the largest reptiles, capable of reaching 7 feet and 1,500 pounds or more. Shaped like a giant, hydrodynamic teardrop, leatherbacks can dive to more than 3,000 feet — deeper than most whales — to eat jellyfish, their main food source. When feasting on these gelatinous invertebrates in the subarctic, leatherbacks keep their bodies warmer than the surrounding water, thanks to their huge body mass and a sophisticated circulatory system. This special adaptation, called gigantothermy, allows these creatures to go where other reptiles would freeze and extends the range of the species to the point that it’s one of the widest-ranging animals. They are citizens of the world: Indonesian leatherbacks travel to Monterey Bay, Calif., to forage, while Trinidad’s leatherbacks visit eastern Canadian waters in the summer. One tagged on Panama’s Caribbean coast was later found alive in a net in Italy and successfully released.

Our adventure with that lost leatherback on our first morning in Trinidad capped off what would be the first of several grueling all-nighters on our trip. While I have photographed them underwater where I live in Florida, I didn’t have any photos of nesting leatherbacks. When one of my buddies with local connections in Trinidad suggested we head down there, I agreed immediately. During peak nesting season in May and June, some of the busiest beaches in Trinidad receive nearly 400 nesting turtles every night.

For the next week we settled into a demanding routine: After dinner we and our guides would head out in pairs to local beaches to work. The red glow of our headlamps revealed clusters of leatherbacks — completely oblivious to our presence — entering and leaving the pounding surf and sometimes even crawling over each other and accidentally destroying nests. These excursions were arduous. The uneven terrain, heat, sand, darkness, smell (from broken eggs and dead embryos), rain and biting insects made it extremely tough to remain focused.

We would return to our simple accommodations in the morning for breakfast, showers and sleep. Random turtles nesting under the blazing tropical sun or unlucky hatchlings being devoured by vultures and frigatebirds broke the midday quiet and made us scramble for our cameras. In the late afternoons we explored the coastline by boat with fishermen, who took us to a staging area offshore where leatherbacks gathered by the dozen prior to storming the beach at nightfall.

During our long boat rides the fishermen described the challenges of making a living during nesting season, unfortunately one of the best times to fish. Almost every time we went out on the water someone at the fishing station was repairing nets that had been ripped apart by 800-pound turtles. Scott Eckert, leatherback expert and director of science at Wider Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network, reports that each year about 3,000 leatherbacks get entangled in gillnets in Trinidad’s waters, with a mortality rate of 33 percent, or 1,000 turtles. Local conservation organizations are working with fishermen to develop fishing techniques that minimize bycatch, but it’s a long and difficult process.

It would be hard to convince the average tourist visiting Trinidad during nesting season that leatherbacks are endangered. Entanglement in fishing gear, coastal development, poaching, boat collisions and the ingestion of plastic bags (mistaken for jellyfish) all take a huge toll. But there is some good news: While the Pacific population is in extreme distress, the Atlantic and Caribbean population appears to be on the rebound. In 2013 the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) upgraded the status of these giants from “Critically Endangered” to “Vulnerable,” because of the recovery in the Western Hemisphere population. Let’s hope conservation and educational programs continue to bear fruit and that leatherback numbers recover throughout their entire range.

Note: All flash and underwater photography of leatherbacks in Trinidad were conducted with permits and with guides from local authorities and sea turtle conservation organizations.

Explore More

Learn more about what is being done to protect leatherback turtles by watching the United Nations video Trinidad: Saving the Turtles.

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2016